POLICY PAPER - FREEDOM

Australia is an international outlier, keeping refugees in detention with no effective independent oversight, minimum standards, or timeframes. There needs to be urgent and systemic reforms to the immigration detention regime to ensure people seeking asylum are treated justly, humanely, and fairly.

The following policy position focuses on the policies implemented by successive governments and how they affect thousands of people seeking asylum and refugees subjected to detention both onshore and offshore. It will also make urgent recommendations and explain how these can be

implemented.

Recommendations

1) Medically evacuate people held offshore on Nauru & Papua New Guinea (PNG), including family members, to safety in Australia for urgent medical treatment, and provide them with necessary supports and a clear and swift pathway to permanency for those who do not have resettlement options.

2) End the policy of sending people seeking asylum by sea to offshore detention, and process applications for protection in the Australian community. People found to be refugees should be permanently and swiftly resettled.

3) Legislate a 90 day timeframe limit on detention.

4) Repeal the mandatory visa cancellation regime and reform the discretionary visa cancellation process to ensure that Australia’s international obligations, connection to the Australian community and family unity are afforded greater consideration. This includes not sending people to third countries such as Nauru and PNG again.

5) Establish a Royal Commission into Australia’s immigration detention regime.

Policy Achievements

Evacuations from Nauru in 2023

People exiled to Nauru in 2013 and kept there for over a decade were finally medically evacuated to Australia by June 2024, leaving behind an empty detention centre. While it was not the end of offshore detention, it marked the end of a dark chapter. Over the decade prior, consistent pressure from the community and the resistance of refugees themselves saw hundreds of people evacuated from offshore detention to Australia.

Christmas Island emptied

The Christmas Island detention centre was emptied in 2023, with all remaining detainees brought to the Australian mainland. But the centre will remain open as a contingency. When Labor came to government in May 2022, there were 1,414 people in immigration detention, a figure that fell to 1,079 in July 2023 due to fewer visa cancellations on character grounds and community release for some low-risk detainees.

Historic High Court ruling on indefinite detention

In November 2023, the High Court of Australia ruled that it is unlawful and unconstitutional for the Australian government to detain people indefinitely in immigration detention if there is no real prospect of their removal from Australia in the reasonably foreseeable future.

The ruling overturned a 20-year precedent, and the 2004 case of Al-Kateb v. Godwin, which had upheld the constitutional validity of indefinite immigration detention. It was a win for the human rights and dignity of refugees and people seeking asylum. As a result, around 300 people were released from detention into the Australian community.

Onshore detention releases

With the Labor government purporting that “immigration detention is a last resort”, the overall number of people in immigration detention has decreased. As of February 2025, there were 980 people in onshore detention. The overall number of people in immigration detention, including in the community under residence determination, has decreased by 24 to 1104, compared with 1128 at the end of February 2024 and 1534 on 28 February 2022 (under the Liberal government).

Landmark UN Human Rights Committee Decision

In January 2025, the UN Human Rights Committee ruled that Australia breached a human rights treaty, and is responsible for the arbitrary detention of people who sought safety here and were exiled to offshore detention, and has a duty of care to them. This landmark decision was made after the Australian government transferred 25 refugees and people seeking asylum to Nauru, some of whom were unaccompanied minors. The UN recommended that the Australian government promptly compensate people for violating their human rights, provide permanent protection in Australia for people who are still, after many years, on bridging visas, many with no pathways to resettlement.

Background

Australia continues to operate a policy of offshore processing of people seeking asylum who arrive by sea without a visa. Of the 3,129 people sent to Manus Island and Nauru between July 2013 and mid-2014, approximately 900 transferred to Australia are in limbo with no permanent status, and 37 remain stranded in Papua New Guinea (PNG). In addition, since transfers to Nauru recommenced in September 2023, as of 2025, there are currently 94 refugees and people seeking asylum detained in Nauru with limited support.

The harm of offshore detention is well known, with over 14 deaths, documented child abuse, physical and sexual assault, medical neglect, and a history of urgent court injunctions for the medical transfer of hundreds of people to Australia. Australia’s offshore policy has been widely condemned, repeatedly coming under criticism from the United Nations, national and international human rights organisations. To spend even $1 keeping someone in these conditions for one day would be a national shame. Since the policy was introduced in 2012, successive governments have now spent over $13 billion on offshore processing. In the 2024-25 budget, the government set aside $604.4 million for offshore processing, or $6 million per person detained on Nauru. The Australian government has allocated $581 million for offshore processing in the 2025-26 budget.

Nauru

People on Nauru are arbitrarily and indefinitely detained. Some have already been recognised as refugees; however, there are currently no resettlement options available to them. They have not been given any information about timeframes for their detention. Upon arrival, they are offered return-resettlement packages and have reported feeling pressured to return to their country of origin. Returns have occurred, and there has been no transparency around assessments of the risk of harm of return.

People are receiving $230 per fortnight to cover their basic needs, including food, drinking water, and internet, a rate that has not increased for years, despite the rising cost of living on Nauru. Consequently, they cannot afford to eat 3 meals a day, to buy fruit, vegetables, and meat. People are relying on fishing to supplement a lack of access to food. With no access to clean drinkable water, people rely on boiling water to drink.

A 2024 ASRC health paper found that of a sample of 66% of people held on Nauru, 65% reported suffering physical health conditions, 22% suffer severe mental health conditions, and 10% suffer from suicidal ideation. People on Nauru have expressed concerns about the lack of healthcare available to them, with no after-hours or weekend primary care, delayed access to specialist assessment and treatment, and no inpatient psychiatric care facility.

Case study

Mohammad is a refugee in his thirties detained on Nauru, and is separated from his wife and two young children.

He has been unable to find work and struggles to survive on $230 per fortnight financial allowance he receives. He cannot afford to eat 3 meals a day, and to buy fruits, vegetables and drinking water. He relies on fishing to supplement his diet, and boiling water to make it drinkable.

As a result, Mohammad is suffering from concerning weight loss, a lack of nutrition, as well as depression, and a skin condition due to the hot, humid weather in Nauru.

Mohammad has been waiting for months to see a skin specialist. He is eligible for resettlement, but as time passes, without any clear information about his future, Mohammad’s depression and hopelessness are worsening.

Mohammad is detained arbitrarily and indefinitely, and must be prioritised for resettlement immediately.

PNG

The Australian government exiled approximately 1,353 people to the Manus Island detention centre in 2013. Nearly 12 years later, there are 37 refugees remaining, many with partners and children, now in Port Moresby. Subjected to long-term detention, family separation, human rights abuses, medical neglect, and ongoing uncertainty, the majority of people are extremely unwell and traumatised. Refugees have suffered an enduring health crisis, and the threat to life and safety becomes more critical by the day.

The 2024 ASRC health report revealed shocking statistics – of those we are in contact with, 100% of refugees suffer from physical health conditions, 40% suffer chronic suicidality and a history of suicide attempts, and 20% are at imminent risk of loss of life. Many refugees have severe physical conditions and debilitating mental health conditions. A small group are acutely mentally unwell, frail, terrified, paranoid, and unable to care for themselves or consent to receive support.

Refugees continue to face barriers to accessing healthcare. This precarious situation is causing significant distress, physical and mental health deterioration for the group, and a risk of loss of life. Resettlement to date has been minimal and drawn-out, and people are becoming too unwell to engage in the resettlement process.

Case study

Anwar is a refugee in his fifties, who is so unwell that he is unable to engage in any resettlement pathway and fears that he will die in PNG.

Anwar suffers from a myriad of debilitating physical and mental health conditions and requires a high level of medical support, which has not been given to him in PNG. He had to arrange his own medical equipment to monitor his health daily. Anwar recently had a range of negative experiences with Pacific International Hospital (PIH) staff denying him medical treatment. His physical and mental health have continued to decline due to the ongoing stress and trauma of being held offshore for several years, and should he not receive adequate physical and mental health care, the consequences will be dire.

Anwar is too unwell to comprehend signing the agreement for the new program of support and is therefore without a financial allowance. He has at times been without food, healthcare and medications. He has been transient and relocated to accommodation many times. This precarious situation is compounding all of the other risks to Anwar’s health and safety.

Anwar’s family have been torn apart due to Australia’s immigration policy. He has some family in a refugee camp in Asia, and a son with a disability in another country who is being supported by the UNHCR. Anwar does not know if he will meet his family again. He has no social support in the community and is isolated. Anwar has a poor quality of life and continues to deteriorate, resulting in impaired decision-making capacity, such that he is now too unwell to engage in any resettlement pathway. Anwar requires urgent medical investigation and treatment not available in PNG.

Medical evacuation is the only option to save Anwar.

People seeking asylum found to be refugees who arrived on Nauru after September 2023 are eligible for resettlement; however, they are effectively stuck in indefinite detention, as currently, there are no resettlement options available for them.

Of the 37 people stranded in PNG, over half are in a resettlement pathway. However, resettlement to date has been minimal, bureaucratic, and drawn-out, with many refugees too unwell to engage in the process. Unless they are urgently evacuated to Australia and their resettlement is prioritised, the threat to life and safety becomes more critical by the day.

Dozens of refugees subjected to offshore processing, in limbo on bridging visas in Australia, expected to resettle in the United States, have been affected by the Trump Administration’s freeze on refugee programs. The Canadian private sponsorship program is no longer accepting applications.

Whilst the Australian government is in discussions with the New Zealand government regarding extending the resettlement program, it is currently set to end at the end of June 2025.

Consequently, there will be no resettlement options available for approximately 900 transitory people on rolling short-term bridging visas – many with no work rights, no study rights, and no access to a social safety net or mainstream support services.

As of February 2025, there are 980 people in onshore immigration detention facilities across Australia, 5 of whom are children.

The time people spend in immigration detention has rapidly increased since 2012, when people spent an average of 100 days in immigration detention in Australia. In 2024, people seeking asylum were held in detention for 1,006 days on average. By contrast, the average length of time in detention in 2023-24 was 49 days in the USA and 16 days in Canada.

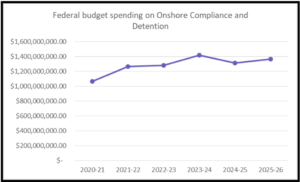

In the 2025-26 budget, the Government has allocated $1.37 billion to maintain an increasingly cruel onshore immigration detention regime. This is an increase from the $1.31 billion budgeted in 2024-25.

According to Federal Budgets, the cumulative spending on onshore and offshore detention between 2015-2023 was over $18 billion. This is equivalent to building a new state-of-the-art 1,000-bed public hospital in every state and territory or funding the ABC for the next decade and a half.

On the individual level, the spending also shows that there are clear alternatives. To keep people held in immigration detention, including Alternative Places of Detention (APOD), the average administered cost per person in 2022-23 was $505,176. In contrast, the average administered cost of a person seeking asylum living in the community on a bridging visa was $2,575. This is approximately 0.5% of the cost of keeping someone in detention.

NZYQ High Court Decision

On 8 November 2023, the High Court of Australia held that indefinite immigration detention (where there is no end point in a person’s detention) is unlawful and that the Australian Government cannot detain a person if they cannot be removed from Australia.

NZYQ is a pseudonym used to refer to a stateless Rohingya refugee from Myanmar. The Department of Home Affairs agreed that NZYQ was owed protection from Myanmar and could not be returned there. The Department also had not found another country to remove NZYQ to, which meant he could not be removed from Australia. The Court ordered that NZYQ be released and that his detention was unlawful.

In response, in November 2023, the government passed a new law that applies to people released from detention because of the NZYQ High Court decision. The law says that people released will be granted a Bridging Visa R (BVR) with additional conditions, including curfew requirements and electronic monitoring devices.

Following the NZYQ High Court win, there was government and media hysteria. Politicians incited panic amongst the general public, raising concerns about community safety. Members of Parliament continue to use fear and division and to demonise people seeking asylum for political gain.

Labor’s brutal bills

The introduction of three new laws passed in late 2024 expanded the Minister’s powers to deport people from Australia, reverse protection findings for a larger group of people than previously allowed, and prevent people from certain countries from entering Australia. These new laws also enable the Government to impose curfew and ankle monitoring conditions for BVR holders.

The Migration Amendment Act, the Migration Amendment (Removals and Other Measures) Act, and the Migration Amendment (Prohibited Items in Immigration Detention) Act are the most significant changes to the way we treat refugees since offshore detention was introduced. They attack the freedom, human rights, and safety of migrants, refugees, and people seeking asylum.

The ASRC strongly opposes these new laws and advocates for their immediate repeal. These laws have already enabled the Government to attempt to deport members of the NZYQ cohort to Nauru, announced in February 2025. This attempt sets a dangerous precedent, raising serious concerns about human rights and fairness.

These powers and the move to deport people contradict recent national polling, which found that the majority of voters do not want to send people seeking asylum back to dangerous situations or to pay other countries to take people who are currently seeking asylum in Australia.

How to achieve change

You can support current ASRC campaigns calling for the government to immediately evacuate all refugees and people seeking asylum from PNG and Nauru for urgent medical care. https://action.asrc.org.au/health-crisis

The ASRC is also campaigning for the government to honour its clear duty of care to refugees in PNG and prioritise their resettlement. https://action.asrc.org.au/refugees-off-png