Part II: Coalition’s radical new policy is no solution

Last week, the ASRC revealed the inaccuracies in Morrison’s announcement of a radical shift in the Coalition’s refugee policy (see Part I). His major new proposal was to refuse Afghan asylum seekers who arrive “illegally” in Australia and subsequently exchange them for refugees in camps bordering Afghanistan. In last week’s blog, we debunked two of Morrison’s justifications for this new proposal: overcrowding and stopping boats to save lives. This week we look at the oft repeated myth about queue jumping and how the Coalition’s real agenda is to shift Australia’s burden of responsibility to the developing world.

Queue Jumpers

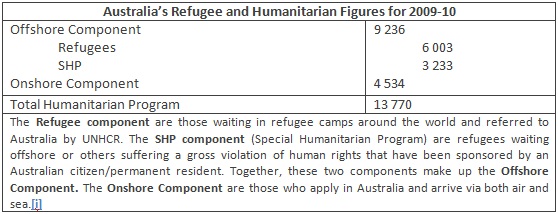

In Morrison’s speech to the Lowy Institute, he asserts that boat arrivals force other refugees to wait “in even more desperate situations” in offshore camps. In fact, it is government policy that does so. Australia denies one spot from its offshore program for every successful onshore applicant who arrives by either air or sea. No other country in the world links its onshore and offshore program in this way. The policy could easily be changed so that Australia accepts all successful onshore applicants in addition to the number of offshore places already dedicated. This would not result in unsustainable numbers. If such a policy had been in place last financial year, Australia would have received a maximum additional 4543 refugees. That would take the total number to 18313 as opposed to the 13770 actually taken. This is still well below what most other refugee receiving countries accept and still less than the UN recommended 20 000 places, or 0.1% of our population.

Not fair

Another of Morrison’s diversionary assertions is that the acceptance of onshore arrivals produces “fundamentally inequitable outcomes” because they are the ones with the greatest “mobility and capacity to pay” and thus are processed in advance of those who are “less mobile and less able to organise international travel.” His solution is to return back to the refugee camps those Afghans who gain entry to Australia “illegally” and exchange them for those already assessed by UNHCR as in need of resettlement to ensure everybody is provided with equality of treatment.

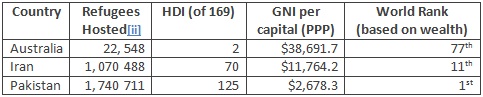

However, while it may be true that onshore asylum seekers are more mobile, Morrison fails to acknowledge that secondary movements arise primarily because the disproportionate burden of protecting refugees falls on countries least able to assume them. So while Pakistan and Iran have generously opened their borders to millions of Afghan refugees for decades, the financial and social strain on these developing economies has resulted in a failure to provide the basic human necessities for vast numbers of people. Around 5 million refugees in the world are in protracted situations where their basic rights and essential economic, social and psychological needs remain unfulfilled after years in exile. Many refugees in these countries still face protection issues that equal those they originally fled. Under such conditions, it is only natural that asylum seekers will attempt to look elsewhere for adequate protection.

‘Equitable treatment’

For Morrison to cry foul and force these asylum seekers back to such conditions is not an act of “equitable treatment” but a further contribution to the injustice already inflicted. It’s as if in an emergency evacuation where there’s only one bus out of town, the state emergency services decide to rescue no one so that everyone is treated equally – even if this means no one is treated justly. Morrison does not want Australia to be a country of first asylum for Afghans, but instead a place that is reserved for resettlement only. Asylum seekers should be kept “as close to home as possible,” he says, ostensibly to facilitate their return. Of course, “close to home” means the developing world because that is where most asylum seekers originate, and resettlement ultimately shifts the reception and processing costs to those first or third countries of asylum. Hence, a closer look at Morrison’s so called solution reveals not a concern for a more “equitable outcome” but an intent to shift responsibility away from the developed to the developing world.

UNHCR notes that since the 1990s it has experienced budget shortfalls as donor countries have become less willing to share the refugee burden assumed by host countries in the developing world. Until that time when Australia and the rest of the international community pull their weight to lift the burden from the countries of first asylum, they have no moral grounds for refusing to accept the trickle of refugees who present themselves at their doorstep.

[i] Figures taken from DIAC’s latest annual report 2009-10.

[ii] Figures taken from UNHCR Global Trends Annexes (2009). Note that UNHCR uses the number of onshore arrivals over 10 years for industrialised countries in order to get a more accurate picture of the relative burdens held by developed and developing countries.

Leave a reply

Connect with us

Need help from the ASRC? Call 03 9326 6066 or visit us: Mon-Tue-Thur-Fri 10am -4pm. Closed on Wednesdays.