Australia’s failure to protect: Sri Lanka and Human Rights

Since the end of the 20- year civil war between the Singhalese and the Tamils in 2009, there has been a surge in Sri Lankans who fear persecution by the Sri Lankan government seeking refuge in Australia. In response to the increase of Tamil Asylum Seekers in particular the government has implemented a policy of “advanced screening” process that operates to circumvent due process to properly assess the verity of their claim for Refugee Status. The gradual implementation of this policy has seen Australia go from granting 100% of Primary Protection visas sought by Sri Lankan Irregular Maritime Arrivals (IMAs) in Dec 2011, to 16.4% in September 2012 and down to 8.8% for the first quarter of 2013[1].

The Migration Act does not have any instructions on how to conduct an initial screening process of IMAs when they first arrive in any of the excised territories of Australia (as of May 2013 this included mainland Australia). Instead the Federal government relies on its own policy initiative during the initial assessment, which under this new advanced screening process, denies legal representation and gives no information to Asylum Seekers of their rights unless they specifically request for it. Under this highly secretive screening process for IMAs the Australian Government has subjected many asylum seekers to extra-rapid[2] deportations without a formal assessment of their claims.

The lack of transparency in the governments advanced screening process became more apparent after the treatment of the Tamil IMAs who arrived by boat at Geraldton Harbor, Western Australia in April 2013. Thirty-eight of those who arrived seeking asylum were flown back to Sri Lanka’s capital Colombo. Immigration Minister Brendan O’Connor claims that they had been returned because they did not, in their initial assessment, raise issues of Australia’s obligations under international law (i.e they had not made an immediate claim for refugee status).

This is a precarious position to take legally and morally, as we could be sending back asylum seekers after only an initial assessment even though they might be found to be genuine refugees if they were granted a formal assessment or on appeal. This is especially true in light of the fact that 80% of protection visa refusals are overturned after an independent review. [3]

Instead those who most likely would be found to be refugees are returned because they do not assert their legal right to be processed as asylum seekers even though they are denied the right to legal advice or representation in these initial assessment and therefore may not know of their rights for a formal assessment. According to Gillian Briggs, President of the Australian Human Rights Commission such a policy could violates the principle of Refoulement under International law. The principle of Refoulment is enshrined in Article 33 of the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, obliging Australia as a member state to ensure that we do not return or ‘refouler’ a refugee to their home country if their life or freedom would be threatened. By sending the 38 Tamils back to Sri Lanka, under the ‘advanced screening’ process and denying them the right to a formal assessment and the appeals process, we are potentially involuntarily returning individuals who may have a legitimate claim for refugee status. In the last 6 months, of the 1071 Sri Lankans returned, 682 have been returned involuntarily. [4]

The April 2013 Amnesty International Report on Sri Lanka[5] supports many of these asylum seekers claims that Tamils and dissenters of the majority Singhalese Government are being persecuted – and that many Sri Lankan asylum seekers have a well founded fear of persecution if they return to Sri Lanka. According to the Amnesty Report, since the end of the civil war the Sri Lankan government has institutionalized breaching its citizen’s rights as its Constitution allows for laws to be made that derogate from fundamental rights such as freedom of expression, right to equality, freedom from discrimination and freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention in the interest of ‘national security’. There are multiple findings in the Amnesty Report of Sri Lankan government officials (including Special Task Force and members of the Presidents Security Division) intimidating, kidnapping and torturing journalist, NGO members and its own civilians who criticize or vocalize their dissent of the Sri Lankan governments human rights record.

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay has joined Amnesty in criticizing the state of Sri Lankan governments human rights abuse putting Sri Lanka in the same category as Rwanda, Iraq and Afghanistan. Human Rights Watch has also released a report detailing how rape has been used as a tool of torture to extract forced confessions of those suspected to be associated with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) who fought against the Sri Lankan Government during the civil war. Despite this report detailing 75 individual accounts of Tamil civilians abducted and subjected to government sponsored rape and torture until they signed a confession admitting that they were part of the LTTE, the Sri Lankan Government refuses to accept any findings that criticize their actions during or after the civil war. In light of such findings, it is possible that any number of the 38 individuals who were denied a formal assessment of their claim of refugee status would have been found to be a genuine refugee in need of Australia’s protection against systemic and entrenched abuse due to their race and/or political opinion. Instead, they have been sent back where there is a substantial possibility that their life and freedom will be threatened.

In a May 2013 decision, lawyers went to court seeking an order that would grant them access to Sri Lankan asylum seekers .[6] Once again, spokespeople for the Immigration Department repeated that the government does not have to provide free legal assistance unless specifically asked for. The judge in this case contrasted the situation of Asylum Seekers to prisoners who in comparison were allowed weekly access to free legal aid. Fortunately, lawyers were granted access to the asylum seekers so that they could assist them prepare for their refugee status claim.

It is troubling that the Immigration Minister believes that legal representation for Asylum Seekers can be denied simply because they do not officially request one. The Immigration Minister and the Federal Government needs to ensure that we do not continue to fail in protecting one of the most vulnerable groups in society by continually to restrict their access to legal aid and using the guise of an ‘advanced screening’ process to deny them the right to have their case heard formally.

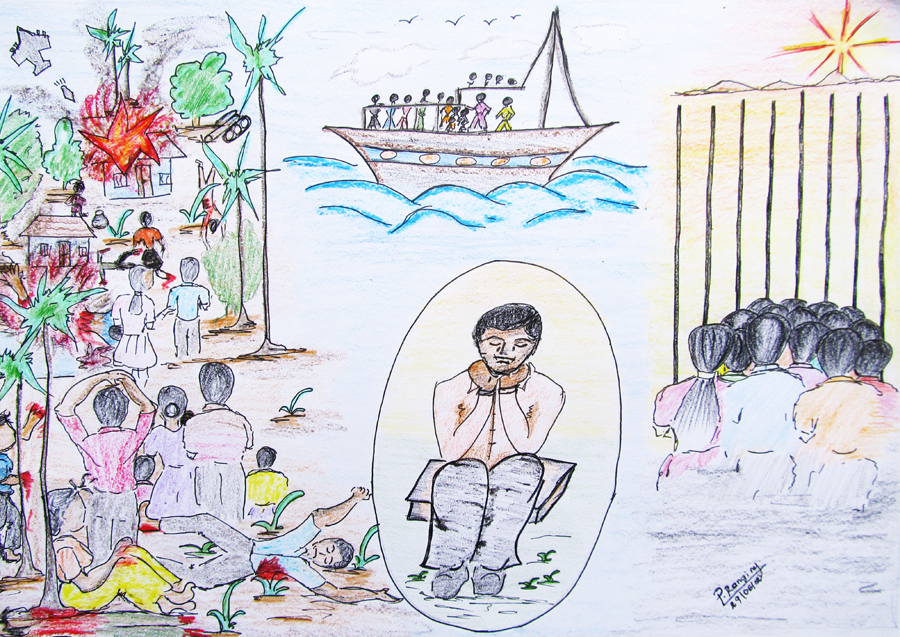

Top image “Ranjini, ‘A Life of Grief'”, as part of the Refugee Art Project – www.therefugeeartproject.com

[1] Department of Immigration and Citizenship ‘Asylum Statistics- Australia. Quarterly Tables – March Quarter’

http://www.immi.gov.au/media/publications/statistics/asylum/_files/asylum-stats-march-quarter-2013.pdf, pg 15

[2] Andrew Crook, ‘Screened out asylum seekers sent home without info’ http://www.crikey.com.au/2013/04/24/screened-out-asylum-seekers-sent-straight-home-without-info-review/? wpmp_switcher=mobile

[3] Human Rights Law Centre, ‘Screening out Asylum Seekers undermines the rule of law and risks returning people to face torture’ http://www.hrlc.org.au/screening-out-asylum-seekers-undermines-the-rule-of-law-and-risks-returning-people-to-face-torture

[4] Minister for Immigration and Citizenship, ‘Minister to visit Sri Lanka from May 2-4th’ http://www.minister.immi.gov.au/media/bo/2013/bo202305.htm

[5]Amnesty International, ‘Sri Lankas Assault on dissent’

http://www.amnesty.org.au/images/uploads/news/4081_sri_lanka_april2013.pdf

[6] The Age, ‘Tamil Asylum Seekers granted lawyers after court plea’ http://www.smh.com.au/opinion/political-news/tamil-asylum-seekers-granted-lawyers-after-court-plea-20130524-2k5r0.html

Leave a reply

Connect with us

Need help from the ASRC? Call 03 9326 6066 or visit us: Mon-Tue-Thur-Fri 10am -4pm. Closed on Wednesdays.