‘Enemy alien’: an Australian refugee story

By Joan, ASRC volunteer and refugee rights advocate.

My family was Austrian, and I was born on 4th of October, 1935. Hitler had been appointed Chancellor of Germany in January 1933 and achieved full dictatorial control by August 1934. Austria hadn’t yet fallen to the Nazis, but it was only a matter of time. Four years, in fact.

Up until 1938, life seemed to have a certain rhythm. My father worked in his family’s wine and export business and my mother worked alongside her father in a Scholl shop in the heart of Vienna. Being ethnically Jewish didn’t mean much until Nazism began to take a hold.

Being ethnically Jewish didn’t mean much until Nazism began to take a hold.

The rise of Nazism came slowly, and then all at once; an unnoticed accumulation of side-ways looks, insults under the breath, broken windows. Small acts of violence growing larger, until eventually, inevitably, something had to give. While the Nazi Party never gained the popular vote, intimidation and threats from Hitler across the border and the strength of the Austrian Nazi movement ultimately lead to what was essentially, a surrender to Hitler.

The rise of Nazism had a particularly strong effect on my mother. She used to say that she wanted to go ‘as far away as one possibly could.’ She had seen photos of Australia – endless blue skies, sunshine, yellow wattle – and she thought it was perfect. Beautiful and far, far away.

After recently reading Klaus Neumann’s Across the Seas – Australia’s Response to Refugees, I realise just how lucky we were. Fortuitously, the Australian government accepted applications for a visa for our family because my father offered a job as a wine expert despite the official policy in Australia, which was often to refuse Jewish refugees.

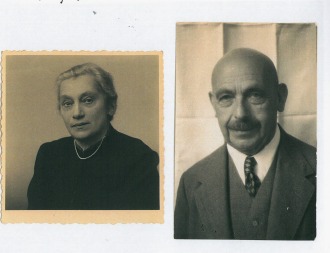

My maternal grandparents were forced to leave Vienna after my grandfather was released from prison. They went to Prague, and when they wanted to leave for the UK, the airport was shut down. Consequently they were deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp, in Czechoslovakia where my grandfather starved to death and my grandmother was subsequently deported and murdered in Auschwitz, Poland.

We left Vienna in August 1938 and flew to London. The night before we left, my father was arrested. He was only allowed to join us if he signed an agreement promising to never return to Austria. He signed it.

The night before we left, my father was arrested. He was only allowed to join us if he signed an agreement promising to never return to Austria. He signed it.

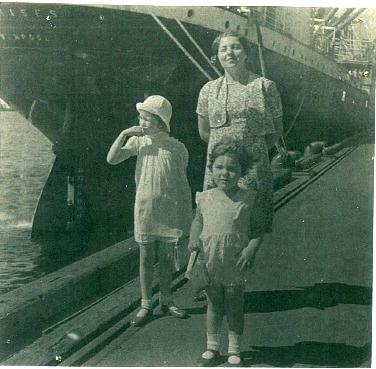

We arrived in Perth in January, 1939 to find a letter informing us that my father’s job was no longer available. Two weeks later, we were in Adelaide being greeted by a Rabbi and several Jewish women. Somehow, miraculously, my mother was offered a job as a chiropodist and Scholl representative in a shoe store in the city. We decided not to continue on to Sydney where dad’s job was no longer waiting, and stayed in Adelaide.

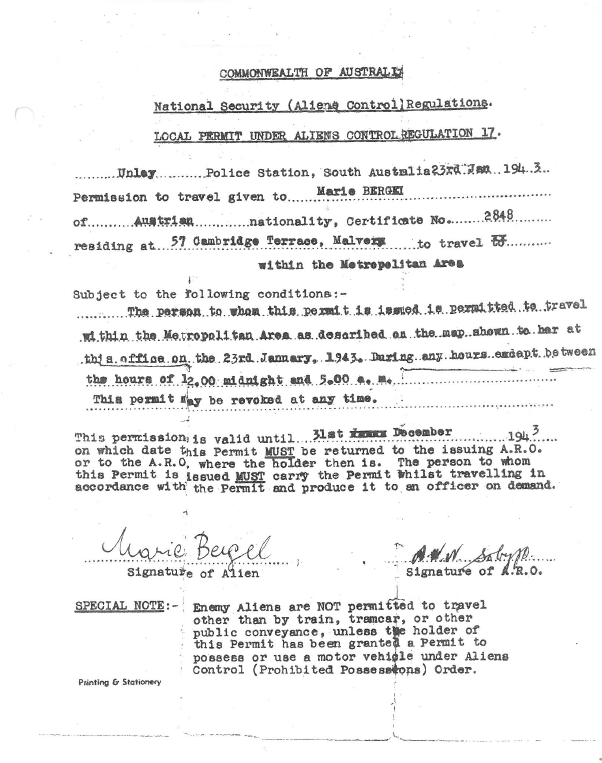

Even though we were refugees fleeing Nazism, we were deemed ‘enemy aliens’ and my parents had to report to the police each week.

Even though we were refugees fleeing Nazism, we were deemed ‘enemy aliens’ and had to report to the police each week. We were restricted as to where we could travel and weren’t permitted a radio or telephone. We were constantly in fear of being sent into the country – it had happened to other families. I still have letters that my father wrote, begging to be permitted to stay. I was sent to a boarding kindergarten which was free for young refugee children while parents went to work.

In another miracle, we were given the opportunity to rent a house attached to a corner milk bar. Not only did we now have food and a roof over our head, we had a livelihood. My mother moved her chiropody practice to the store as well.

My parents often describe how friendly and kind everyone was to them while the war was being fought in Europe.

Like all people seeking asylum – the loss of family, one’s home and the history that one leaves behind weighs heavily on a person’s ability to rebuild their life. But what we also left behind was the fear of war and anti-Semitism. We left in search for peace and safety, and we certainly found that in Australia. This is why my story reflects so much found in refugee stories.

Since volunteering at the ASRC fourteen years ago, I understand more fully just how lucky we were. We were never locked up or sent to another country like some refugees are now. It’s so hard to make sense of why people seeking asylum are treated the way they are now. My family was afforded the safety that is a fundamental human right for all people found to be refugees and for which we were and still are extremely grateful.

#TheirStoryOurStory

At some stage in our history, a family member has sacrificed something so that the we, or the next generation could feel safe, loved, and to prosper. These stories recognise the importance of giving a person the opportunity to feel safe, and build a better life.

Leave a reply

Connect with us

Need help from the ASRC? Call 03 9326 6066 or visit us: Mon-Tue-Thur-Fri 10am -4pm. Closed on Wednesdays.