POLICY PAPER - FAIRNESS

Everyone should be entitled to live with dignity and in safety with their families. However, refugees and people seeking asylum are often denied these basic rights in Australia.

Permanent protection is essential for refugees to reunite with their families and rebuild their lives with certainty and hope for their future. A swift pathway to permanent residency is a humane and fair response for people seeking asylum who have been subjected to the unjust Fast Track process and waiting over a decade for their protection visa application outcomes to be finalised.

Refugees and people seeking asylum have also suffered devastating consequences due to Australia’s broken refugee status determination process, including refoulement and permanent family separation. Unfair processes, poor decision-making and lengthy delays have plagued the refugee status determination process, and immediate action is required to mitigate further harm to refugees and people seeking asylum.

Informed by people with lived experience of seeking asylum, this policy position paper will address urgent reforms to ensure pathways to permanency and establish a fair and efficient refugee status determination process.[1]

[1] For information on Australia’s immigration detention regime and refugees’ exclusion from mainstream social support, please refer to the ASRC’s policy position papers on Freedom and Safety respectively.

Recommendations

- Provide a clear and swift pathway to permanent residency to all people seeking asylum subjected to the Fast Track process.

- Provide all people seeking asylum with access to a fair and efficient refugee status determination process, including the introduction of the ‘90 day rule’ regarding processing timeframes and access to procedural safeguards in merits review.

- Abolish temporary protection visas and provide permanent protection to all refugees.

- Increase government-funded legal representation to people seeking asylum throughout the refugee status determination process, including merits review and judicial review stages.

Policy Achievements

The ASRC’s 2022 fairness policy paper included these recommendations which have been achieved.

On 13 February 2023, the Albanese Government announced that TPV and SHEV holders would be eligible to apply for permanent Resolution of Status visas (RoS Visa) from March 2023. The Government estimated that the majority of RoS Visa applications would be finalised within 12 months from a person’s RoS Visa application date. As of 31 July 2024, over 18,500 RoS Visas have been granted.

In February 2023, the Albanese Government abolished Ministerial Direction 80, a policy which discriminated against refugees who arrived by sea by deprioritising their family visa applications. Under the new policy, Ministerial Direction 102, all families will be entitled to have their family visa applications dealt with under the usual processes, regardless of how they travelled to Australia.

In May 2024, the Albanese Government passed legislation to replace the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) with the Administrative Review Tribunal (ART), which abolishes the Immigration Assessment Authority (IAA) and Fast Track process.[2] The establishment of the ART will address concerns regarding protracted delays and bias, including a transparent and merit-based system of appointments. The ART will commence on 14 October 2024[3], and cases before the IAA at this time will be transferred to the ART for finalisation once the ART is established.

These changes are important steps towards establishing a fair and efficient refugee status determination process. However, the ART legislation maintains an unfair and different set of rules for refugees, people seeking asylum and migrants which must be reformed.

[2] Administrative Review Tribunal Act 2024 (Cth), Administrative Review Tribunal (Consequential and Transitional Provisions No. 1) Act 2024 (Cth).

[3] Attorney-General’s portfolio, Administrative Review Tribunal to commence in October, 19 July 2024, https://ministers.ag.gov.au/media-centre/administrative-review-tribunal-commence-october-19-07-2024.

In October 2023, the ASRC welcomed the Government’s announcement of over $48 million for legal representation for protection visa applicants.[4] However, the details of how this funding has been allocated and how many people seeking asylum have been able to access legal representation through this funding have not been published. It remains to be seen whether the recent funding will significantly improve access to legal representation for people seeking asylum, particularly people with higher barriers to access to justice such as those in immigration detention.

[4] The Hon Andrew Giles MP, Restoring integrity to our protection system, 5 October 2023, https://minister.homeaffairs.gov.au/AndrewGiles/Pages/restoring-integrity-protection-system.aspx.

The Government has increased funding to address backlogs before the Department, merits review and courts regarding protection visa applications. In October 2023, the Government announced a $160 million package to address visa processing delays.[5] Further, the 2024/45 Federal budget included an investment of $854.3 million over four years for the roll-out and sustainable operation of the ART, and $115.6 million over four years from 2024–25 (and an additional $194.2 million from 2028–29 to 2035–36) to address high migration backlogs in the federal courts, including through the establishment of two migration hubs dedicated to hearing migration and protection matters.[6] Adequate resourcing to ensure timely outcomes is an integral part of a fair and efficient refugee status determination process.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Refugee Council of Australia, The 2024-25 Federal Budget: What it means for refugees and people seeking humanitarian protection, 14 May 2024, https://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/the-federal-budget-what-it-means-for-refugees-and-people-seeking-humanitarian-protection/ (RCOA 2024-25 Federal Budget Analysis).

Background

Between October 2013 and December 2014, the Abbott Government amended Australia’s laws to prevent people who sought asylum by sea from accessing permanent protection in Australia. This affected approximately 31,000 people, including those who sought asylum by sea between August 2012 and December 2013, people who sought asylum by sea before this period whose protection visa applications were not finalised, and children born to the families in this cohort (known collectively as the ‘Legacy Caseload’). People in the Legacy Caseload were only eligible to apply for temporary protection visas, namely Temporary Protection Visas (TPVs) and Safe Haven Enterprise Visas (SHEVs).

Most people within the Legacy Caseload were also subjected to the ‘Fast Track’ review process. Fast Track is a misleading name for the slow and defective refugee status determination process for people who sought asylum by sea and arrived after August 2012. Under the Fast Track process, if a person seeking asylum had their protection visa application refused by the Department, they can only seek limited merits review before the Immigration Assessment Authority (IAA). The IAA is a review body within the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT), which is responsible for independent merits review of administrative decisions made by the Australian Government.

The Fast Track process has failed on many levels – it has produced unfair and legally incorrect decisions, exposed refugees to refoulement, caused protracted delays and re-traumatised people seeking asylum.

The IAA is not required to observe minimum standards of procedural fairness. IAA decisions are generally based on a paper review of information before the Department, and people seeking asylum do not have a right to a hearing to present their protection claims. Applicants are only allowed to provide a five-page submission, which must be provided within three weeks from the date their case is referred to the IAA from the Department.

Consequently, the IAA’s decision-making has been unjust and riddled with errors. Since 2020, over 34% of IAA decisions (i.e. over 460 decisions) reviewed by the courts were found to be unlawful[7]; many people would not have been able to access judicial review or legal representation, meaning the number of unlawful decisions is likely to be considerably higher. There is a real concern that the Department’s errors are not rectified through the review process, with the IAA effectively acting as a rubber stamp for the Department by affirming close to 90% of Department decisions.[8]

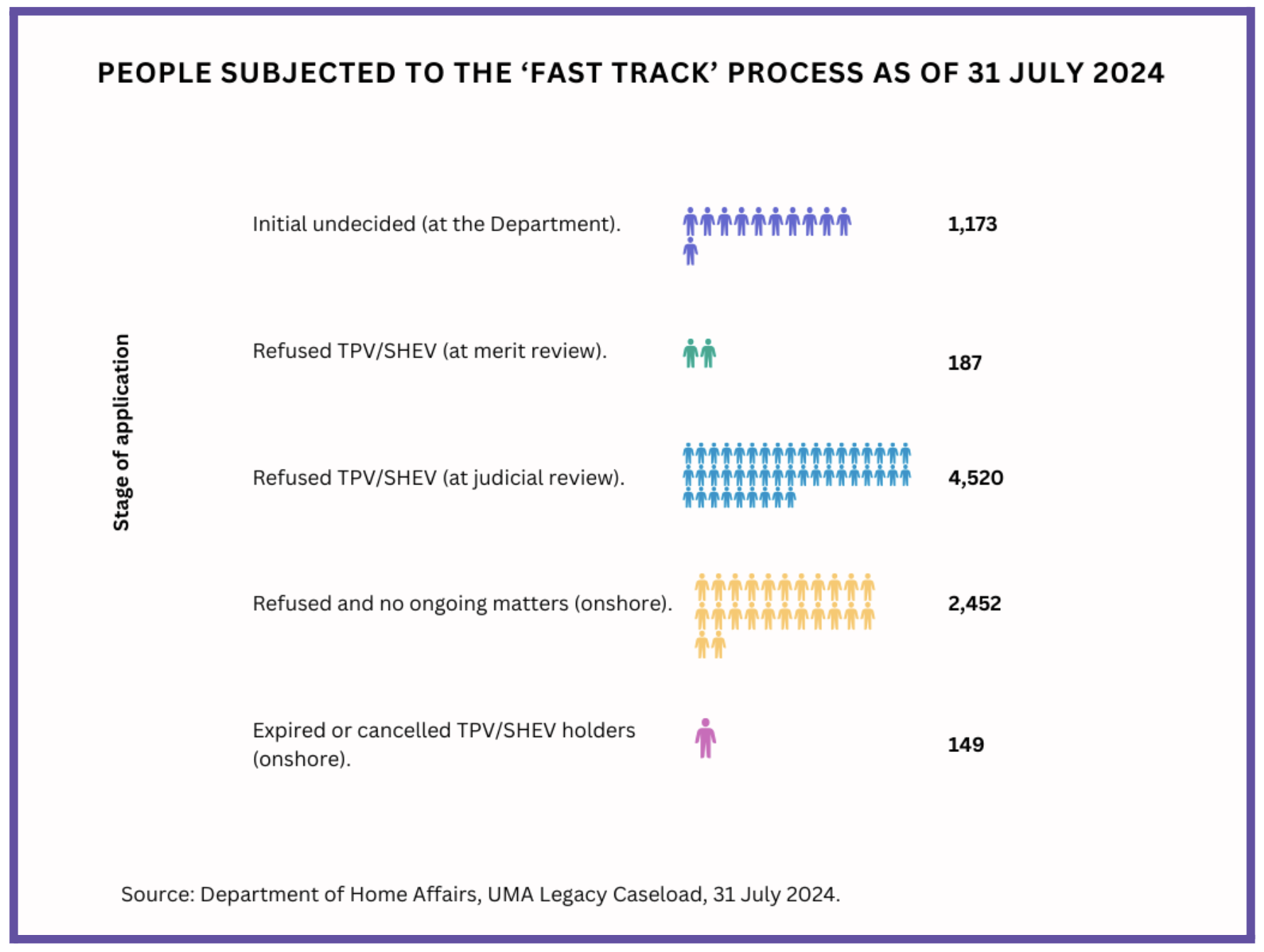

In February 2023, the Albanese Government announced a pathway to permanent residency for TPV and SHEV holders (many of whom had been subjected to the Fast Track process). This pathway is via an application for a Resolution of Status Visa (RoS Visa). People within this cohort could apply for a RoS Visa from March 2023. However, the Government’s announcement excluded approximately 7,300 people seeking asylum, who are not TPV/SHEV holders and have been exposed to the unfair Fast Track process and living in Australia for over 10 years.[9]

Over 4,700 people excluded from the Government’s announcement are still being dragged through the unfair Fast Track process; they will only be eligible for a RoS Visa if they are found to be owed protection obligations by the IAA, often after waiting years for court decisions that may be reached without legal representation.

The Government will abolish the IAA and establish a new and fairer review body, the Administrative Review Tribunal, from 14 October 2024. However, until this date people will not have access to a fair review process. Also, the new Tribunal will not fully remedy the injustice experienced by people exposed to the unfair Fast Track process, in particular for people who no longer have a review process on foot and cannot benefit from the new Tribunal.

Case Study Anjali fled Pakistan in 2013 and sought asylum with her husband in Australia. They had a daughter soon after they arrived in Australia, and their family applied for a protection visa. Anjali was subjected to family violence by her husband and they separated. Anjali’s case was refused by the IAA and she sought judicial review of her IAA decision. Anjali was not able to raise new information about the family violence she experienced before the Courts as they can only consider information that was before the IAA. Anjali could not afford legal representation for her court case, and her case was dismissed by the Courts. Anjali’s daughter became an Australian citizen last year after being born in Australia and living here for 10 years. However, Anjali does not have a pathway to permanency to live in Australia as her child’s sole carer after seeking asylum for over a decade. |

The Albanese Government has stated that an unsuccessful Fast Track applicant who has new protection claims could request the Minister to intervene in their case and allow them to apply for another TPV or SHEV.[10] This is an inadequate response. The avenues for ministerial intervention are limited, rarely successful and at best enable someone to submit a further protection visa application rather than being granted a visa. This is not a clear and swift pathway to permanent residency.

Case Study Ahmad arrived in Australia in 2013 after fleeing Iran. Ahmad’s protection claims relate to his statelessness and ethnicity. He applied for a SHEV in 2017, which was unsuccessful, and sought merits review before the IAA. The IAA did not accept that Ahmad was stateless and found that he is an Iranian citizen. Ahmad sought judicial review of his IAA decision, however he could not afford legal representation and was unsuccessful before the courts. Ahmad managed to obtain evidence from the Iranian authorities that he is not an Iranian citizen. In July 2022, Ahmad sought Ministerial intervention under section 48B of the Migration Act as he had updated information about his protection claims and statelessness. After two years, Ahmad has not received any update about his Ministerial intervention request and is living in uncertainty about his future. |

The pathway to permanency for this cohort should not be limited to further assessment of their protection claims. It is grossly unfair to expect everyone in this cohort to still meet this threshold over 10 years after they fled their countries of origin. The Department’s processing times for TPVs and SHEVs ballooned to over six years,[11]which is the main reason why people are still waiting for a permanent solution over a decade later. Also, people have been subjected to protracted delays in seeking review of protection visa refusal decisions, with the courts still processing judicial review applications that were lodged over seven years ago in 2017. People should not be punished for the Government’s bureaucratic failure and ineffective processing, which caused excessive delays that prevented them from obtaining a fair and final outcome for their protection visa applications.

Case Study Joseph fled Sri Lanka in 2013 and sought asylum. His SHEV application was refused by the Department and IAA, and he sought judicial review. Joseph has faced multiple processes before the IAA and court. He is awaiting the outcome of a judicial review matter of his third IAA decision and has been seeking asylum for over a decade. Even if Joseph is successful before the courts again, highlighting the repeated failure of the IAA to determine his claim lawfully, he is unlikely to obtain a positive outcome due to the protracted delay which has impacted his protection claims. |

People subjected to the unfair Fast Track process have been living in Australia for over a decade – they have been working, paying taxes, attending school and rebuilding their lives. After seeking asylum for over 10 years, living with uncertainty and being separated from their families, the moral and humane response is to provide a pathway to permanent residency for all people seeking asylum impacted by the unfair and cruel Fast Track system.

Recommendation 1: Provide a clear and swift pathway to permanent residency to all people seeking asylum subjected to the Fast Track process.

[7] Administrative Appeals Tribunal Annual Reports 2021-22 and 2022-23, Chapter 4 – Immigration Assessment Authority, https://www.transparency.gov.au/publications/attorney-general-s/administrative-appeals-tribunal/administrative-appeals-tribunal-annual-report-2021-22/chapter-4-immigration-assessment-authority/performance; https://www.transparency.gov.au/publications/attorney-general-s/administrative-appeals-tribunal/administrative-appeals-tribunal-annual-report-2022-23/chapter-4-immigration-assessment-authority/performance (appeals remitted in relation to total appeals finalised).

[8] Ibid.

[9] Additionally 1,173 people have not received an initial decision from the Department, which increases the total number of people failed by Fast Track to approximately 8,500.

[10] Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs, Explanatory Statement – Migration Amendment (Transitioning TPV/SHEV Holders to Resolution of Status Visas) Regulations 2023, 13 February 2023, https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2023L00099/Download, p. 14.

[11] Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee, 2022-23 Budget estimates October and November, OBE22-177, https://www.aph.gov.au/api/qon/downloadestimatesquestions/EstimatesQuestion-CommitteeId6-EstimatesRoundId19-PortfolioId20-QuestionNumber177.

People seeking asylum should have access to a fair and efficient refugee status determination process. Australia’s current system fails to meet this standard – it denies procedural fairness and is overly bureaucratic, which has resulted in protracted delays, unjust decisions and devastating impacts on people’s lives.

In May 2024, the ASRC welcomed the long-overdue passage of legislation to replace the AAT with the Administrative Review Tribunal (ART), which abolishes the IAA and Fast Track process.[12] The Fast Track system discriminates against certain people seeking asylum based on their mode of arrival to Australia; however, all people seeking asylum should have access to a fair and efficient refugee status determination process regardless of how they came to Australia. The establishment of the ART will also address concerns regarding protracted delays and bias, including a transparent and merit-based system of appointments. The ART will commence on 14 October 2024, and cases before the IAA and AAT at this time will be transferred to the ART for finalisation.

Fix protracted processing delays

One of the key reasons that Australia’s refugee status determination process has failed people seeking asylum is lengthy processing delays. In 2018-2019, the average time for the Department to process a permanent protection visa application was 334 days; by 2022-23 this had more than tripled to 1,076 days.[13] Lawyers at the ASRC have observed that it can take one to three years for an applicant to be invited to a Department interview, and even when a person is found to be owed protection, it can take an additional year for the protection visa to be granted.

If a person’s permanent protection visa application is refused by the Department, then they must contend with extraordinary delays seeking review before the AAT/IAA and the courts.[14] These delays mean that a person seeking asylum could wait over a decade for a final visa outcome.

Protracted delays cause significant distress to people seeking asylum as they are unable to plan with any certainty for their future. It denies them the right to rebuild their lives and reunite with family and exacerbates mental health issues, which in turn can impact on their ability to engage in the refugee status determination process. Also, lengthy processing times force people seeking asylum into destitution because they are denied mainstream social support and often do not have work rights.[15] Timely decision-making which does not compromise on quality and fairness is essential to uphold the rights of people seeking asylum to ensure they can live in safety and with dignity.

Case Study Benjamin arrived in Australia on a student visa after fleeing his country of origin due to facing serious harm because of his sexuality. He was unaware that he could apply for a protection visa on these grounds. Benjamin’s mental health declined due to his trauma. He was unable to meet his student visa requirements and his student visa was cancelled. Benjamin experienced homelessness and was extremely unwell. He was taken into detention; at this time he was connected with the ASRC and he applied for a protection visa and was released from detention on a bridging visa without work rights. Benjamin waited over five years for his protection visa to be granted and could not work during this time or access Medicare despite his complex health needs. Benjamin applied for work rights on his bridging visa several times, but the Department refused to grant him work rights because it did not consider that he had an ‘acceptable reason’ for his delay in applying for a protection visa. The protracted delay and lack of work rights caused immense distress and exacerbated Benjamin’s mental health conditions and made it very difficult for him to engage in the protection visa application process. |

The Albanese Government has started taking steps to address these issues, including the abolition of the AAT, establishment of the ART and increased funding to address backlogs before the Department, Tribunal and courts regarding protection visa applications. However, the Government must take further steps to avoid this situation again and ensure additional funding for visa processing is responsibly managed to reduce delays. Clear guidelines to ensure timely refugee status determination processing and accountability towards these standards are required for meaningful and lasting change.

The 2023 ALP platform commits to reintroduce the ’90 day rule’.[16] The rationale for this rule was included in the 2021 ALP Platform as an accountability measure to ensure that all refugee status determinations are concluded in a timely way within 90 days.[17] This legislative standard will reduce the risk of Australia repeating its past mistakes, and ensure that people seeking asylum have certainty regarding the timeframes for protection visa processing.

Remove barriers to procedural fairness in merits review

The abolition of the IAA and AAT and end of the Fast Track process are important steps towards establishing a fair and efficient refugee status determination process. However, the ART legislation maintains an unfair and different set of rules for refugees, people seeking asylum and migrants which must be reformed. These laws also disproportionately impact the most disadvantaged people in our community, such as women fleeing gender-based violence and people with severe mental health conditions.

For example, section 367A in the Migration Act requires the ART to draw an unfavourable inference where a protection applicant raises new claims or evidence before the ART if the ART is satisfied the applicant does not have a reasonable explanation for this delay.[19] Protection visa applicants have valid reasons for a delay in providing updated evidence and claims, including trauma and related mental health illness, language barriers, fear of authorities and lack of legal representation. As the legislation does not provide any guidance regarding what would suffice as a ‘reasonable explanation’, there is no guarantee that these valid explanations would be accepted by the ART. Consequently, this provision is likely to continue to cause severe hardship and unfair outcomes for protection applicants. There is no valid justification for including this requirement, especially as Tribunal members already have discretion to assess any delay as part of an applicant’s credibility within their existing powers.

Case Study Mindy came to Australia from Nigeria on a student visa. She applied for a protection visa as she was fearful of domestic violence from her family. Mindy is lesbian, however she was afraid and ashamed to disclose this to the Department, especially as she was worried her family in Nigeria might find out. Mindy’s protection visa was refused by the Department and she sought review before the Tribunal. Mindy accessed pro bono legal representation, and received legal advice about raising protection claims regarding her sexuality. However, the Tribunal was required to draw an unfavourable inference against Mindy when she raised her sexuality claims for the first time, which unfairly disadvantaged Mindy and led to an unjust outcome. |

Another significant barrier for people seeking asylum to access merits review is the ART’s inability to extend deadlines for reviewable migration and protection decisions, which unfairly disadvantages migrants and protection applicants.[19] This law is discriminatory as the ART has the power to extend deadlines for other types of applications. Refugees and people seeking asylum often face additional barriers to seeking review within the standard 28-day timeframe, including immigration detention, language barriers, insecure housing and employment, serious mental or physical illness, and other unforeseen circumstances (e.g. fraudulent migration agent or legal representation), and should have the ability to request an extension of their deadline to seek review. The ASRC regularly assists protection visa applicants who have missed their AAT deadline to seek review for very legitimate and unforeseen circumstances, and suffer the unjust consequences of losing the right to seek merits review. Their only recourse is to seek judicial review before the High Court of Australia, which is costly and not available for the majority of people.

Case Study The ASRC represented Kamal who missed his deadline to seek review before the AAT by one day due to a miscalculation of the timeframe because of how the 28-day deadline is calculated (by including the date of notification). Kamal’s Department decision regarding his Protection visa refusal was clearly affected by error, however he could not seek merits review. The ASRC represented Kamal before the High Court of Australia, and his matter was successful and remitted to the Department. Had Kamal not been able to access legal representation (including payment of the High Court fees) by the ASRC, he would have been returned to his home country and faced persecution. A remedy came at significant public cost and after delay, causing harm and distress. |

The ASRC’s submissions to the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee Inquiry regarding the Administrative Review Tribunal Bill 2023 and related bills include detailed recommendations to ensure merits review is fair and accessible to people seeking asylum.

Recommendation 2: Provide all people seeking asylum with access to a fair and efficient refugee status determination process, including the introduction of the ‘90 day rule’ regarding processing timeframes and access to procedural safeguards in merits review.

[12] Administrative Review Tribunal Act 2024 (Cth), Administrative Review Tribunal (Consequential and Transitional Provisions No. 1) Act 2024 (Cth).

[13] Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee, 2022-23 Budget estimates October and November, OBE22-180, https://www.aph.gov.au/api/qon/downloadestimatesquestions/EstimatesQuestion-CommitteeId6-EstimatesRoundId19-PortfolioId20-QuestionNumber180.

[14] As of March 2023, processing times for AAT protection cases could take up to 2,021 days – see Administrative Appeals Tribunal, Migration and Refugee Division processing times, 2023, https://www.aat.gov.au/resources/migration-and-refugee-division-processing-times. Also, migration cases at the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia have increased nearly threefold over the last decade from 1,981 in 2012-13 to 5,236 in 2020-21. Generally applicants seeking judicial review at court of their Protection visa decision wait at least two to three years for their matter to be finalised.

[15] For more information refer to the ASRC policy position on Safety.

[16] Australian Labor Party, ALP National Platform – As Determined by the 49th National Conference, 2023, p 141.

[17] Australian Labor Party, ALP National Platform – As Adopted at the 2021 Special Platform Conference, 2021, p 124.

[18] Administrative Review Tribunal (Consequential and Transitional Provisions No. 1) Bill 2023 (Cth) sch 2 item 170. This clause replicates section 423A in the Migration Act 1958 (Cth).

[19] Administrative Review Tribunal (Consequential and Transitional Provisions No. 1) Bill 2023 (Cth) sch 2 item 160.

The Albanese Government’s TPV/SHEV conversion announcement did not abolish the existence of the temporary protection regime in Australia. In fact, the Government included specific amendments to the Migration Regulations 1994 (Cth) to clarify that TPVs and SHEVs will continue to exist after the conversion announcement.[20] This means that refugees will be subjected to temporary protection in the future – this applies to refugees who arrive in Australia without a valid visa (e.g. people who arrive by sea or people who arrive by plane and their visas are cancelled at the airport because they intend to seek asylum). In contrast, people who arrive in Australia with a valid visa, and then seek asylum are eligible to apply for a permanent protection visa.[21]

A person’s mode of arrival to Australia must not determine their eligibility for permanent protection; this practice is discriminatory, unfair and results in certain refugees being treated as second class.

Australia should have learnt from its past mistakes that temporary protection is harmful. Temporary protection visas were first introduced in Australia in 1999 and were abolished in 2008 due to significant community pressure regarding their harmful impact. A 2006 Senate Inquiry confirmed that temporary protection causes immense suffering.[22] Mental health experts found that refugees on TPVs experienced increased anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder in comparison to permanent protection visa holders.[23] Further, the Australian Human Rights Commission reported that temporary protection creates uncertainty for children, which worsens their mental health and hinders their participation in education opportunities.[24] Despite the overwhelming evidence indicating that temporary protection visas cause devastating outcomes and are bad policy, they were reintroduced by the Coalition Government in December 2014.

The cruelty of temporary protection is heightened by restrictions that prevent family reunion for TPV and SHEV holders, including no family sponsorship and limitations on overseas travel. As a result, families are torn apart and separated for protracted and indefinite periods of time. In 2019, the Australian Human Rights Commission published a report on the impact of the Fast Track process and temporary protection on refugees and people seeking asylum, which confirmed that temporary protection continues to inflict immeasurable harm on refugees.[25] Family unity is essential for refugees to rebuild their lives in Australia. Refugees should not have to choose between living in safety and reuniting with their families.

Case Study Abdul fled Afghanistan due to his Hazara ethnicity and came to Australia by sea in 2013. As Abdul arrived by sea, he required permission from the Minister for Immigration to apply for a visa. In 2017, he was only permitted to apply for a TPV via the Fast Track process. The Department and IAA refused his protection visa application, and Abdul sought judicial review of his IAA decision. The court remitted his matter to the IAA in 2020 and he was granted a TPV in 2021, but was not able to sponsor his wife and children in Afghanistan. He is now waiting for his TPV to be converted to a permanent RoS Visa. Abdul has been in Australia for a decade and unable to reunite with his wife and children during this time. By contrast, Mohammed fled Afghanistan due to his Hazara ethnicity and came to Australia by plane on a tourist visa in 2016. As Mohammad arrived by plane on a valid visa, he was able to apply for a permanent protection visa immediately. His visa application was initially refused by the Department, however he was able to seek review before the AAT with full merits review rights. In 2019, the Tribunal confirmed that Mohammad was owed protection and remitted his matter to the Department. Mohammed was granted a permanent protection visa and he was able to sponsor his wife and children to live in Australia. |

The ALP 2023 Platform acknowledges that people seeking asylum have the right to seek asylum regardless of their mode of arrival, and that seeking asylum is not illegal.[26] Therefore, it is inconsistent for the ALP to maintain temporary protection visas that discriminate against people based on how they arrive in Australia.

Temporary protection is harmful because it creates constant uncertainty and refugees are forced to live in limbo. Australia’s temporary protection regime is also contrary to international law, which provides that temporary protection should only be used in rare circumstances, generally in situations of mass movements of people seeking asylum when individual refugee status determination is impracticable. By contrast, Australia’s temporary protection regime exists solely on the basis that people arrived in Australia without a visa – this is not a legitimate reason to deny permanent protection to refugees. Australia’s temporary protection regime risks breaching international human rights law by denying refugees their right to seek safety and live with dignity.[27]

Recommendation 3: Abolish temporary protection visas and provide permanent protection to all refugees.

[20] Migration Regulations 1994 (Cth), Schedule 1, Item 1403 (3)(ba)(i) and Item 1404 (3)(ba)(i)

[21] Migration Regulations 1994 (Cth), Schedule 1, Item 1401

[22] Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee, Inquiry into the Administration and Operation of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth), 2006, https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Legal_and_Constitutional_Affairs/Completed%20inquiries/2004-07/migration/report/index.

[23] Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, Killedar, A & Harris, P, Australia’s refugee policies and their health impact: a review of the evidence and recommendations for the Australian Government, Volume 4, Issue 41, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1753-6405.12663; Momartin S, Steel Z, Coello M, Aroche J, Silove DM, Brooks R. A comparison of the mental health of refugees with temporary versus permanent protection visas, Med J Aust, 2006, 185(7), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17014402/.

[24] Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, A last resort? National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention, 2004, https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/content/human_rights/children_detention_report/report/PDF/alr_complete.pdf.

[25] Australian Human Rights Commission, Lives on Hold: Refugees and asylum seekers in the ‘Legacy Caseload, 2019, https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/publication/ahrc_lives_on_hold_2019.pdf.

[26] Australian Labor Party, ALP National Platform – As Determined by the 49th National Conference, 2023, p 134.

[27] UNSW Sydney, Andrew & Renata Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law, Temporary Protection Visas and Safe Haven Enterprise Visas, https://www.kaldorcentre.unsw.edu.au/publication/temporary-protection-visas.<

The defunding of free legal representation to people seeking asylum has contributed to unfair and ineffective visa processing, including rapidly increasing delays. Since 2014, successive governments have whittled down legal funding to the Immigration Advice and Application Assistance Scheme (IAAAS), which eventually ceased in August 2022.

In October 2023, the ASRC welcomed the Government’s announcement of a $160 million package to address visa processing delays, including over $48 million for legal representation for protection visa applicants. However, the details of how this funding has been allocated and how many people seeking asylum have been able to access legal representation through this funding have not been published. The ASRC urges the Government to publish data on the allocation and scope of existing government-funded legal representation for people seeking asylum.

The lack of free legal assistance to people seeking asylum has had a devastating impact on their ability to engage with the complex protection visa application process due to barriers including literacy and language skills, poor mental health and isolation from community support, especially for people in immigration detention. Legal representation is critical to people seeking asylum having a fair opportunity to explain their protection claims. People seeking asylum are seven times more likely to have a positive outcome at review stages if they are represented by a lawyer,[29] which is unsurprising given the legal complexities in seeking merits and judicial review.

Case Study Zahra fled Pakistan to escape harm from her abusive husband and her family because she wanted to separate from her husband. Zahra sought asylum in Australia and applied for a protection visa in 2016. Her case was allocated to a male Department delegate. During Zahra’s Department interview, she did not feel comfortable disclosing her protection claims to a man and did not know that she could ask to be interviewed by a female delegate. Zahra also did not know the legal definition of a refugee and thought that saying she did not feel safe in Pakistan would be sufficient to be granted a protection visa. She was also unaware that text messages from her family threatening to harm her would be useful evidence for her case. In 2019, the Department refused Zahra’s protection visa application. Zahra’s friend connected her with the ASRC where she received legal advice about her situation. Zahra was assisted to seek review at the AAT and she had legal representation at her hearing. In 2023, the AAT found that Zahra was owed protection obligations and remitted her matter to the Department, and she was granted a protection visa. If Zahra had had legal representation at the Department stage, it is very likely she would have been granted a protection visa before 2019 and avoided an additional four years of seeking asylum. |

Without legal assistance, people seeking asylum cannot effectively engage in the refugee status determination process, which increases unfair outcomes and creates a high risk of refoulement (i.e. return to a country where they face persecution) with devastating consequences. The risk is particularly great for those facing barriers to access to justice, including women fleeing gender-based violence, people with serious health issues, people experiencing poverty, people in detention, and people who speak languages other than English. Also, a lack of legal representation results in inefficient visa processing and a strain on the Department, review bodies and courts’ resources as greater numbers of people seek review of unlawful Department and merits review decisions.

The ASRC does not receive any Federal government funding, and continues to witness that the demand for free legal advice for people seeking asylum is much higher than the resources available. It remains to be seen whether the recent funding will significantly improve access to legal representation for people seeking asylum, particularly people with higher barriers to access to justice such as those in immigration detention.

Recommendation 4: Increase government-funded legal representation to people seeking asylum throughout the refugee status determination process, including merits review and judicial review stages.

[29] The Conversation, How refugees succeed in visa reviews: new research reveals the factors that matter, 10 March 2020, https://theconversation.com/how-refugees-succeed-in-visa-reviews-new-research-reveals-the-factors-that-matter-131763.

How to achieve change

The following are recommendations on how ASRC’s policy recommendations could be enacted by the current government. However, there are many ways to achieve justice and any pathway to achieve humane and moral treatment of people seeking asylum should be embraced.

People seeking asylum as part of the Legacy Caseload have been denied justice and the ability to rebuild their lives for a decade. During this time mechanisms to ensure permanent protection have been presented, including the Kaldor Centre’s ‘’Temporary Protection in Australia: A reform proposal.’’

Thankfully there are existing systems in place to provide refugees in the Legacy Caseload with permanent visas, with only minor amendments. When the Rudd Government last abolished TPV a new permanent visa was created, the Resolution of Status (Class CD) Visa (RoSV). This RoSV still exists and offers a clear way to rectify the years of harm.

For those who hold a TPV/SHEV, an amendment to Migration Regulations 1994 (Cth) r 2.07AQ(3) 45AA and a bar lift would allow TPV/SHEV to be taken as automatic applications for RoSV.

For those still in the application process amending regulation 45AA would allow them to have their application converted to bean RoSV or PPV application.

For people failed by Fast Track, the government could lift the bar to permit them to apply for RoSV or PPVs.

Outside of the ‘Legacy Caseload’, there is an urgent need for systemic reforms of the refugee determination process. These include but are not limited to legislative change to ensure legal representation, removal of discriminatory policies as well as timeframes on decision marking and responses to applications.

There is also an urgent need to abolish the IAA and substantially reform or reconstitute the AAT to ensure merit-based appointments and efficient processing.

The Minister of Home Affairs can also replace Direction no. 80, ensuring that people seeking asylum can reunite with their families.

The ASRC would like to acknowledge the Wurundjeri and Bunurong people of the Kulin Nation as traditional owners and custodians of the land on which the ASRC stands. We acknowledge that the land was never ceded and we pay our respect to them, their customs, their culture, to elders past and present and to their emerging leaders.

Connect with us

Need help from the ASRC? Call 03 9326 6066 or visit us: Mon-Tue-Thur-Fri 10am -5pm. Closed on Wednesdays.